A Song of Ice

& Diamonds

An Arctic adventure through

Canada’s Northwest Territories

with Lily James, Global Ambassador

for Natural Diamond Council.

Words by: Grant Mobley

There is a point where -40 degrees Celsius aligns perfectly with -40 degrees Fahrenheit. This convergence is rarely contemplated, much less experienced by most. Lily James had never considered this fact until she found herself standing on a frozen lake under the Northern Lights. She faced a cold so intense that despite being wrapped in five layers, any exposed skin risked frostbite within minutes. This venture wasn’t just a journey into the heart of winter’s grasp but a quest to witness the profound impact of natural diamond recovery on this land and its people.

This wasn’t Lily James’ first venture into natural diamond country. As the Global Ambassador for the Natural Diamond Council, the Emmy and Golden Globe-nominated actress had previously traveled to Botswana in 2022, immersing herself in the world’s number one diamond-producing country by value.

“You want to make sure when you’re putting your name to something that there’s more to the story,” James reflected during the trip. Yet, this experience did more than meet expectations. Witnessing firsthand the transformative effect of natural diamonds on communities and environments opened her eyes to the reality of the industry. This is how James found herself in the icy expanses of the Northwest Territories —the globe’s third-largest natural diamond source. Here, James would continue her exploration of the three-billion-year-old gems that have transformed the area.

James touched down in Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories, following a day peppered with connecting flights—a typical ordeal for those venturing to this secluded city, situated nearly a thousand-mile drive from Edmonton, its nearest urban neighbor. Yellowknife is home to half of the territory’s forty-thousand inhabitants. It’s a modest population, especially when considering the vast expanse of the territory, which spans an area comparable to the size of Spain, Portugal, and France combined. Indigenous communities represent the soul of this unique region, making up half of the population and an integral aspect of the Northwest Territories’ cultural and historical tapestry.

Cody Drygeese and the drummers playing at the B. Dene Camp at sunset in the Northwest Territories of Canada.

Nestled beside the world’s tenth-largest lake, Yellowknife boasts a stunning natural backdrop. Excited to meet with locals, James headed to B. Dene, the indigenous-owned camp positioned across the bay in neighboring Dettah. The absence of bridges means it’s not a short journey, yet the subarctic in February has its silver lining—the lake, as big as Belgium, transforms into a solid expanse of ice. James’ car veered down a boat ramp, introducing her to an otherworldly experience: driving across two meters of ice on top of the deepest lake in North America. This surreal passage is difficult to put into words, but for the locals, it was part of daily life. Once across, James stopped at the end of the road, where Kateri Lynn and Cody Drygeese met her. Lynn and Drygeese, both influential in their indigenous community, have made their marks in distinct ways. Lynn became Dettah’s youngest elected councilor and works at the local diamond cutting facility, while Drygeese plays a vital part in the operations of the B. Dene Camp, a family endeavor led by his father. Drygeese also bears a lineage of Dene Chiefs—including his great-grandfather, who held the title during Queen Elizabeth‘s visit to Yellowknife in the 1960s. Together, they ushered James into a sled linked to the snowmobile. With Drygeese at the wheel and Lynn sharing the sled with James, they traveled the last few hundred yards through the thick snow to arrive at B. Dene.

The camp, located at Drygeese’s great-grandmother’s birthplace, is a testament to the region’s enduring customs, featuring log cabins and teepees among snow-covered evergreens. It acts as an educational hub, immersing visitors in the Yellowknives Dene First Nation’s heritage and traditional way of life. Upon arrival, James, welcomed by the warmth of a community gathered around a fire, witnessed the ‘feeding the fire’ ceremony led by respected elder Jonas Sangris, a ritual honoring nature’s elements and ancestors. Everyone participated, adding tobacco leaves to a communal bowl before Mr. Sangris added it to the fire, symbolizing a connection to their ancestors. “The smoke rises to our ancestors, who watch over us,” he said. The ceremony, highlighted by the sound of handcrafted drums and singing, deeply moved James and the others, underlining the deep bond between tradition, community, and the natural environment.

The group retreated to the warmth of the camp’s largest cabin, kicking off the evening with lively dancing initiated by the rhythms of Drygeese and his ensemble. The children, who recognized Lily James as the fairy tale figure from Disney’s Cinderella, were the first to take the floor, setting the stage for a memorable night. Charlene Liske, a community pillar with many roles, including coaching the local girls’ team for the Arctic Winter Games, took center stage. The Arctic Winter Games might sound obscure, but Liske detailed how these competitions, akin to an Arctic Olympics and held biennially since the 1970s, celebrate games rooted in centuries-old indigenous practices, each honing skills vital for survival. One such game, the ‘stick pull,’ mimics the action of catching a slippery fish. With Charlene now holding a stick slick with Crisco to simulate the fish’s texture, Lynn pulls James to the center of the room. Positioned back-to-back, each clutched an end of the greased stick, ready to pull. Lynn claimed the first victory, but James called for a best-of-three challenge and triumphed in the second round. As the decisive round commenced, hands slippery, Lynn secured her victory, besting James in a showdown that left everyone basking in communal laughter.

As the cabin filled with the scent of fish stew and bannock, a comforting biscuit-like bread, Lily James and Jonas Sangris discussed natural diamonds’ impact on the region. Sangris shared his story as the Chief of the Dene First Nation before the diamond discovery. He recounted the early 1990s when economic instability loomed. He sought the wisdom of the elders, whose assurance, “Don’t worry, something will come up,” preceded the discovery of diamonds by merely a year—a moment Sangris still marvels at, as if the elders had foreseen the coming discovery and prosperity. Since 1999, the economic landscape of the Northwest Territories has surged by 80%, a boom credited to natural diamonds. Sangris was critical in negotiating terms with mining companies to ensure the community’s maximum benefit. These agreements prioritized local employment, local procurement, royalties for residents, special taxes, and crucial environmental safeguards. Today, diamond mining is the predominant contributor to the region’s GDP. The dwindling population has rebounded since their discovery, and other thriving industries like transportation, tourism, and real estate have emerged. Sangris exclaims with a smile that natural diamonds are “good for the people of the North…I hope we find more.”

Every natural diamond is one-of-a-kind and demands a tailored approach to maximize beauty.

As night fell, the camp’s festivities wound down, leaving James and the locals closely bonded through shared laughter. Yet, the time had come to journey back to Dettah on the snowmobile, leaving behind the warmth of the B. Dene Camp in search of another millennia-old natural wonder.

James returned along the ice road toward the Arctic Duchess, a historic ship entombed in ice. Launched in 1961 and once visited by Queen Elizabeth II, this vessel now welcomes those eager to explore Arctic wonders and the Northern Lights. With the mercury dipping close to -40, the group sought refuge in a tent on the ice beside the ship when suddenly, it happened. The famed Aurora Borealis, or Northern Lights, began to streak across the sky. Beside Lynn, James watched the sky in awe. She listened as Lynn recounted ancient tales of the Northern Lights—stories of their origins and significance to her people passed down through generations. “That’s our ancestors there; it’s like they’re dancing with us,” Drygeese says. The moment, imbued with magic, naturally connected the journey’s intent: Both the Northern Lights and natural diamonds share an ability to inspire awe, signify beauty, and remind us of the Earth’s capacity to create phenomena.

Two male caribou in the herd spotted on the ice road north of the Gahcho Kue diamond mine in the Northwest Territories of Canada.

A few hundred kilometers north of Yellowknife are the three main diamond mines, including Gahcho Kué—a venture co-owned by De Beers Canada. To reach this remote marvel, James embarked on a brief flight aboard a compact aircraft destined for an ice and gravel runway near the site. The landscape transforms dramatically as we venture further north. Trees become sparse, eventually giving way to an expansive white canvas of ice—the Arctic Tundra, a stark yet mesmerizing wilderness.

“It’s not surprising, when you see the beauty of the landscape, that these beautiful diamonds come from here,” says James. Before landing, the alien terrain reveals the mine, a solitary beacon of human resilience and ingenuity amidst the vastness. The comprehensive facilities at the mine site—ranging from essential services like a fire station and hospital to amenities such as a gym and cafeteria—offer a self-contained community for the hundreds of employees who call this place their temporary home, working two-week shifts before returning home for a two-week break.

Environmental monitors for De Beers, Mason Elwood, and Jarrett Vornbrock invite James along to see their efforts to safeguard this extraordinary environment. The journey takes an exciting turn onto The Tibbitt to Contwoyto Winter Road—The Ice Road popularized by the TV show “Ice Road Truckers.” Funded by diamond companies, it’s the world’s longest ice road, connecting the mines to Yellowknife every winter. This vital artery supports the mines’ yearly operations and provides invaluable access to local and indigenous communities, bridging distances across a landscape and saving days of off-road travel. Come winter, the tapestry of countless lakes here, nestled closely together, transform into a unified frozen expanse punctuated by brief overland crossings. Mason, Jarrett, and the environmental teams traverse this road almost daily, monitoring local wildlife, water quality, and everything to ensure the mine operations have as little environmental impact as possible.

Hours from the mine or any signs of civilization, Mason and Jarrett prepare for a water quality test on a nearby lake, undeterred by the harsh conditions. James, feeling the bite of the coldest temperatures yet, nearly -55 degrees, follows them out. With practiced ease, Mason and Jarrett clear snow to expose the ice, then drill through to access the water below. They lower a device to collect water at various depths destined for comprehensive testing. This rigorous process is replicated for every lake within miles of the mine to ensure its operations don’t affect the water. Mason and Jarrett’s dedication to environmental stewardship under such extreme conditions seems heroic, but they clearly love it. According to Mason, natural diamonds have given him “an incredible opportunity to work in a unique and fantastic place that provides opportunity for folks living here…and provide a way for the natural resources of this landscape to give back to the people.”

While still on the ice road, a message crackled through the radio, hinting at the possibility of caribou ahead. For James, an avid animal lover, the prospect of encountering wild caribou was worth a detour. Monitoring the caribou herds is a critical part of Mason and Jarrett’s responsibilities, ensuring the mining operations had no negative effect on the animals. As James put it, “The animals take precedence; it’s their home first.” Soon, Mason sees the herd near the road, prompting us to stop for a closer view. There, a few dozen caribou, including some adorable calves, trotted a couple hundred feet from us. James and the rest of the group once again braved the cold to get a better look, savoring this rare and beautiful encounter.

Back at the mine, James, in protective gear, explored a workshop with Darcy Sinclair, a figure deeply rooted in the indigenous community and a veteran in diamond mining for 26 years. Walking past trucks with tires twice her height, Sinclair shared his view with James, stating, “Diamond mining is the North’s future.” As Gahcho Kué’s mobile maintenance superintendent, he emphasized safety and the importance of skills training at the mine. Sinclair proudly said, “A lot of friends that have trained to work in the mining sector, now they’re actually running their own business,” underscoring the training’s role in providing versatile skills for various career paths. Reflecting on his transition to diamond mining after losing his job in mechanics, Sinclair acknowledges the pivotal role of natural diamonds in securing not just his future but that of the entire community.

After exploring the origins of natural diamonds, described by De Beers Volcanologist Dr. Crystal Mann as “standing inside an ancient volcano,” James visited the Rio Tinto splitting facility, a key location for sorting rough diamonds from the North like those from Diavik, owned by Rio Tinto. Greeted by Gaeleen Macpherson and Melanie Sangris, James was introduced to the sorting process while awing at the array of rough diamonds before them. Gaeleen, balancing roles at Diavik and as President of NWT Women in Mining, and Sangris, Diavik’s first female Tele-remote Scoop Operator, showcased the rough diamonds, some possibly mined by Sangris herself. They marveled at being the first few to see these diamonds since their formation over 3 billion years ago, a remarkable realization. Sangris’ journey in mining began with the Mine Training Society, underscoring the sector’s positive influence on the community. Before it, “I was having a hard time navigating what to do once I was out of school,” she recounted. James noted that their efforts have increased female participation in mining, with Gaeleen adding, “You hear people say, this has allowed me to stay in the North and raise families and contribute,” a sentiment both mothers agree is invaluable.

Diamond mining is the North’s future.

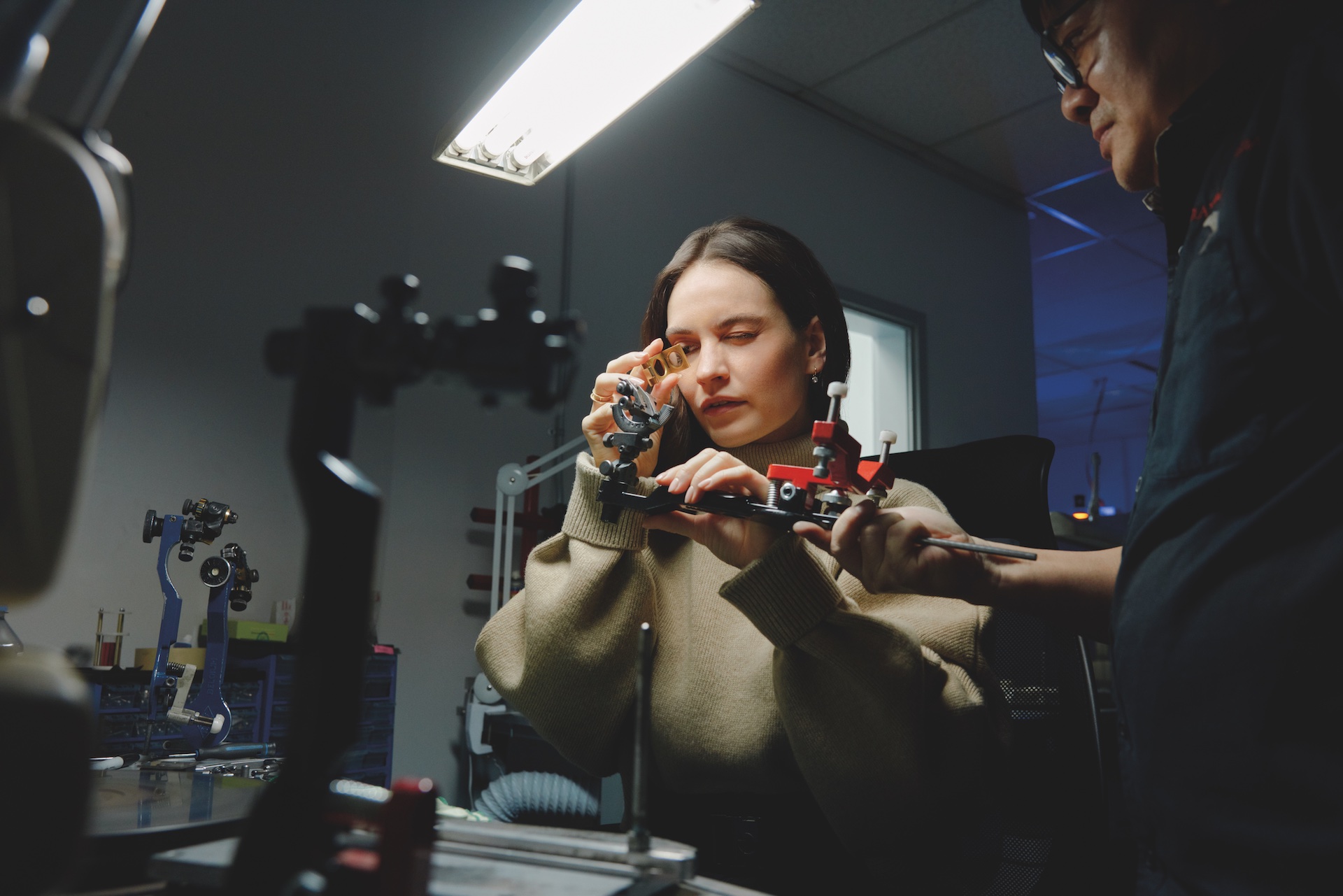

After their initial assessment, expert craftsmen take rough diamonds and sculpt them into the most sparkling version of themselves. Diamonds de Canada is one of these master craftsmen. Kateri Lynn, now a face familiar to James, introduced her to the intricate process. Within the facility, they secured a rough diamond into a device that seemed out of a Star Wars film. She uses the device to scan each diamond to map out an optimal cutting strategy on specialized software. Every natural diamond is one-of-a-kind and demands a tailored approach to maximize beauty. With a clear ‘plan,’ the diamond was entrusted to Derrick Sangris, a maestro of a specialized laser cutting machine. Under his skilled guidance, a precision-guided laser intricately slices through the diamond to make each facet—a process that unfolds over hours. The journey from rough to radiance culminates at the polishing station, where each diamond, its surface roughened by the laser, is polished by hand against a wheel coated in diamond dust. With some help, James excitedly polished one of the diamond facets herself.

Benjamin King, CEO of Diamonds de Canada, explains, “Our cutting facility is not just about transforming rough diamonds; it’s a vital catalyst for generating additional training and employment and enhancing the economic value that natural diamonds provide for the locals in the NWT.”

As the adventure concluded, James and other newfound friends returned to the Arctic Duchess to plunge into the frozen lake on this -30-degree night. Though shocking in its icy grip, this plunge was a moment of clarity and exhilaration. It was a fitting finale to a journey that had unveiled not just breathtaking vistas and the dance of the Northern Lights but also showed the significance of natural diamonds in the area, far beyond being merely an economic cornerstone. Surrounded by the quiet majesty of the Arctic tundra and the camaraderie of those who had shared this unique adventure, Lily James and her companions felt a profound connection to this place. The experience underscored the undeniable truth that natural diamonds, much like the Northern Lights under which they had formed, are not just awe-inspiring phenomena but integral to the fabric of life in the NWT.